Acne is the most common chronic inflammation of the skin, affecting 75% to 95% of teenagers, but it can remain a severe skin problem for adults too. Whereas the typical signs of aging, such as loss of elasticity, age spots, uneven skin tone and wrinkles, are more easily accepted and coped with, acneic skin can have an adverse effect on self-esteem and social relationships.

Prevalence of acne

What has changed in the last decade is that acne, typically seen as a skin condition of adolescence, is now prevalent in more than 50% of adults. This means that many adults have been suffering from acne for a decade or more. This can be partially explained by the fact that a great extent of acne-causing bacteria has evolved to be resistant to antibiotics, and conventional treatments cease to be effective after a few years of use. As prolonged antibiotic therapy in acne treatment is common, antibiotic resistance of Cutibacterium acnes strains (formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes) has been extensively observed[1, 2]. Further, the typical side effects (redness, dryness, irritation) resulting from their use are worse in adult acne sufferers than in teenagers.

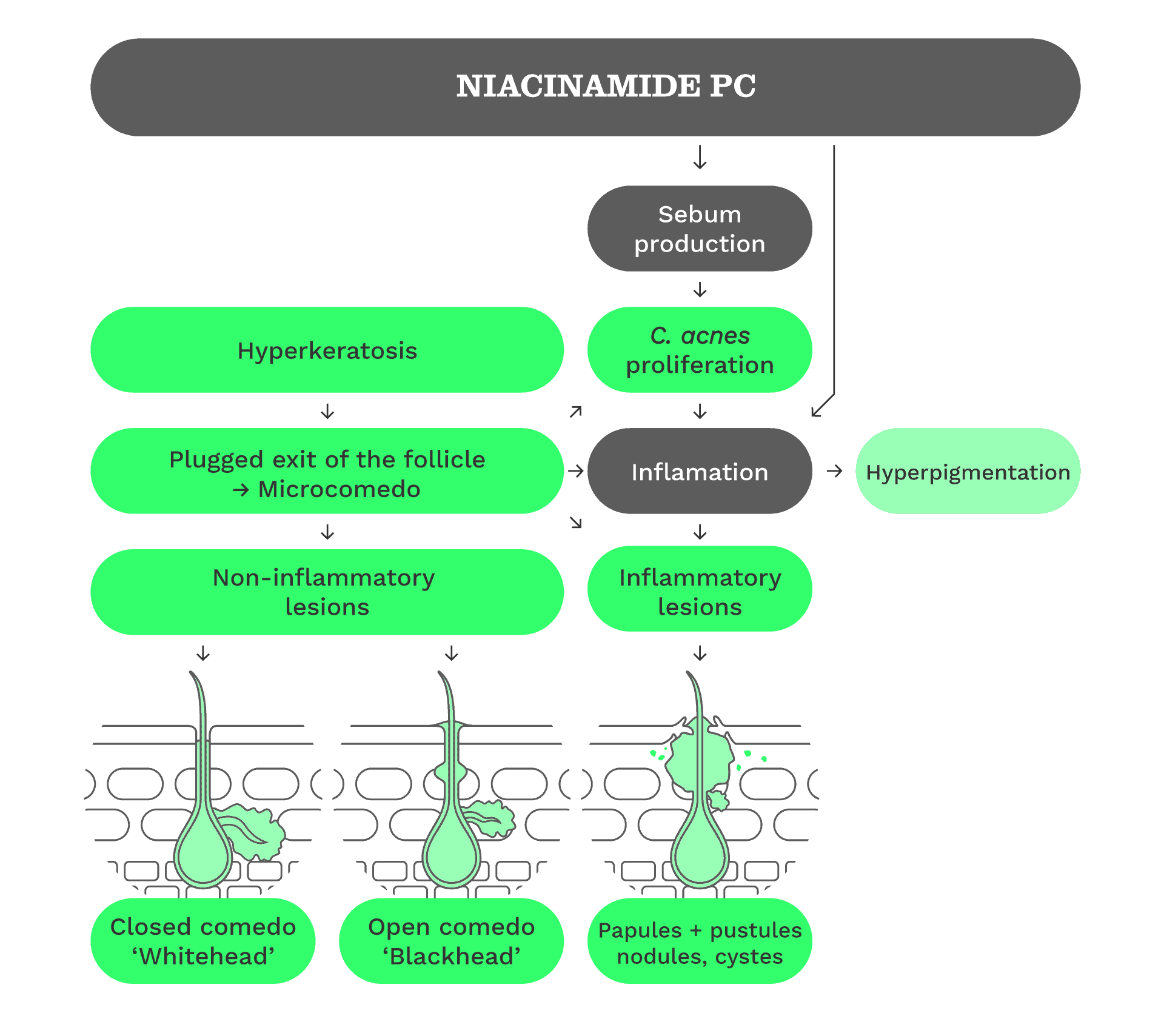

Pathogenesis of acne

Acne vulgaris is a common multifactorial skin disease affecting the pilosabaceous follicles, characterized by non-inflammatory comedones and inflammatory papules, pustules and nodules in its more severe forms.

Four factors are considered to play a key role in the development of acne lesions and exacerbation of acne: excess sebum production, disturbed keratinization within the follicle, colonization of the pilosebaceous duct by pathogenic Cutibacterium acnes strains, and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators into the skin[3].

Androgen stimulation is causative in the acne puzzle as the sex hormone triggers the sebaceous glands to produce more sebum. In parallel, hyperkeratinization blocks the pilosebaceous canal through an excess of keratinocytes which leads to a small swelling, referred to as a microcomedo. If the mouth of the canal remains closed, a so-called whitehead is seen. If the duct dilates and finally opens, oxidation processes create a so-called blackhead. These non-inflammatory comedones – together with the sebum – provide optimal conditions for the anaerobic C. acnes to proliferate. To date, the scientific understanding of the role of C. acnes in the pathophysiology of acne has changed: rather than its hyperproliferation, it is the loss of microbial balance and diversity (a phenomenon called dysbiosis) between the different C. acnes strains (defined as phylotypes) that is associated with acne development[4].

The bacterium is a normal skin inhabitant (commensal) and contributes to the strengthening of the skin’s natural defence mechanisms. However, C. acnes strains belonging to the phylotype IA1 carry an extra set of virulence genes and produce significantly higher levels of the pro-inflammatory metabolites and porphyrins relative to other commensal C. acnes variants[4].

Acne is sometimes followed by mild-to-moderate reactions, such as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

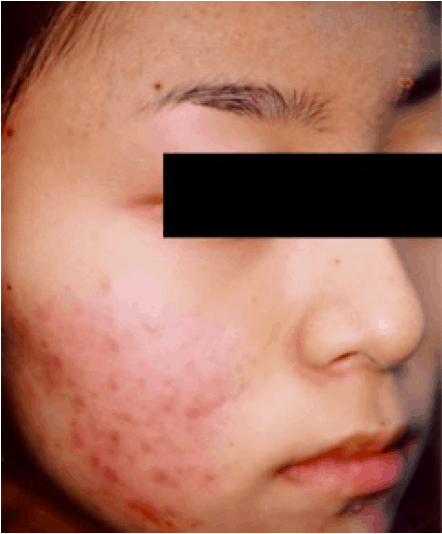

Clinical acne vulgaris

Treatment compliance

Despite the negative impacts of acne vulgaris on mental health and on social relationships, treatment compliance is generally poor. Adolescents often discontinue treatment either when an early improvement is visible, or as soon as there is a perception of worsening acne and when side effects of common topical treatments begin to appear. This suggests that mitigation of side effects as well as anticipatory guidance may contribute to improve compliance. Topical therapies generally consist of either a monotherapy (one single treatment agent) or a combination with multiple topical agents (especially in more severe forms of acne), or they may be combined with oral agents in both initial control and maintenance. However, when multiple therapies are prescribed, the rate of patients – especially adolescents – not redeeming their prescriptions is high[5].

Conventional treatments

The topical therapy of acne vulgaris includes the use of agents that are available over the counter or via prescription. Conventional pharmaceutical acne treatments vary in consumer acceptance and effectiveness, and the results often do not meet the expectations of the patients. Such acne therapies are typically based on retinoic acid, antibiotics or benzoyl peroxide. On one hand, antibiotics used to reduce the population of C. acnes can also harm healthy skin bacteria and disrupt microbiome balance. On the other hand, the use of retinoids and benzoyl peroxide is generally associated with the development of unpleasant side effects, such as skin redness and burning[6]. Some of the reported side effects include increased photosensitivity with possible pigmentation changes.

New opportunities

There is an opportunity to satisfy customer need for milder yet effective acne care that can be easily integrated within the daily beauty regime. A combination of cosmetic ingredients can feature the following advantages:

• Interference with acne pathogenesis at different steps

• Enhanced cosmetic benefits of ‘acne’ products

• Meeting of additional adult beauty desires: anti-ageing, anti-wrinkle effects, even skin tone

• Management of PIH while avoiding disruption of the natural microbiota (unlike antibiotic use, which may increase the risk of colonization by pathogens or the potential for C. acnes to form an antibiotic-resistant biofilm)

Counteracting acne pathogenesis at different levels

Acne pathogenesis can be counteracted in different ways. The targets of anti-acne treatments are the exacerbating factors that so far have been identified, such as excess sebum production, hyperkeratinisation, inflammation and loss of microbial balance following skin colonization by pathogenic C. acnes strains. Salicylic acid is widely used to treat skin conditions such as psoriasis, seborrhoeic eczema, neurodermitis and warts[7]. It has been used as a keratolytic agent since the 19th century, when it was first derived from the bark of the willow tree. In fact, salicylic acid reduces the cohesion between corneocytes, allowing the shedding of dead skin cells. The disadvantage of salicylic acid is that it can cause irritation and disturb skin integrity (through an increase in transepidermal water loss (TWEL)) at low pH. In the following content, we list a series of substances that have been proven to effectively counteract acne pathogenesis at different levels and, at the same time, have the advantage of being free of the typical side effects of conventional treatments.

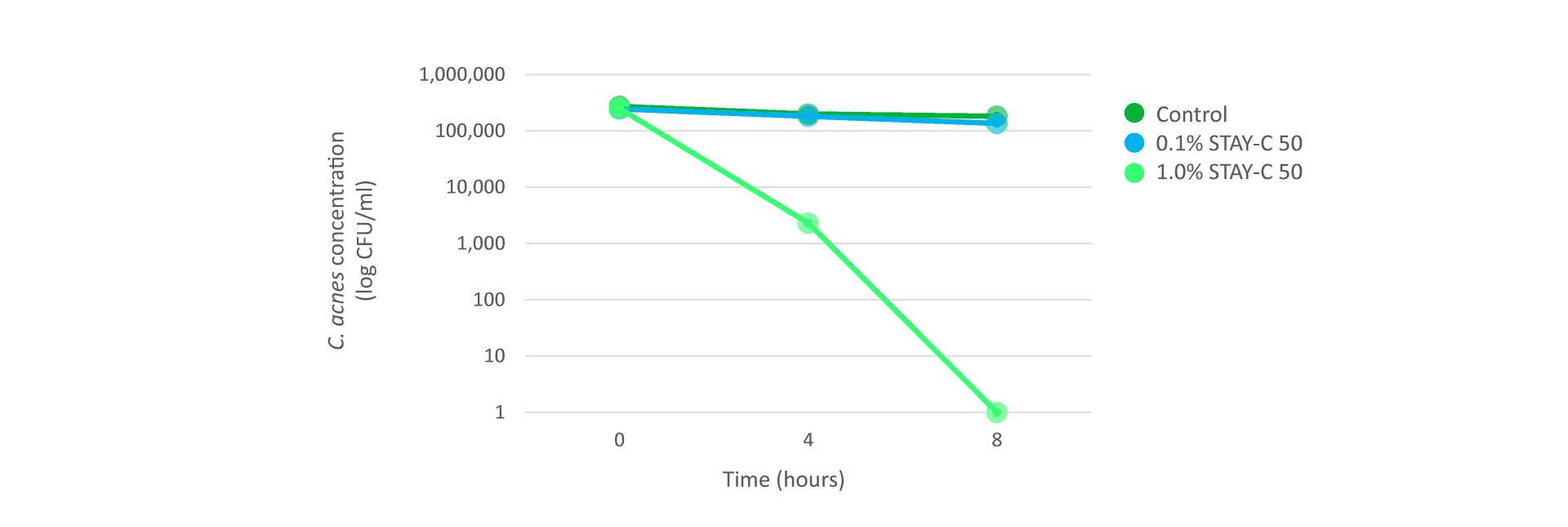

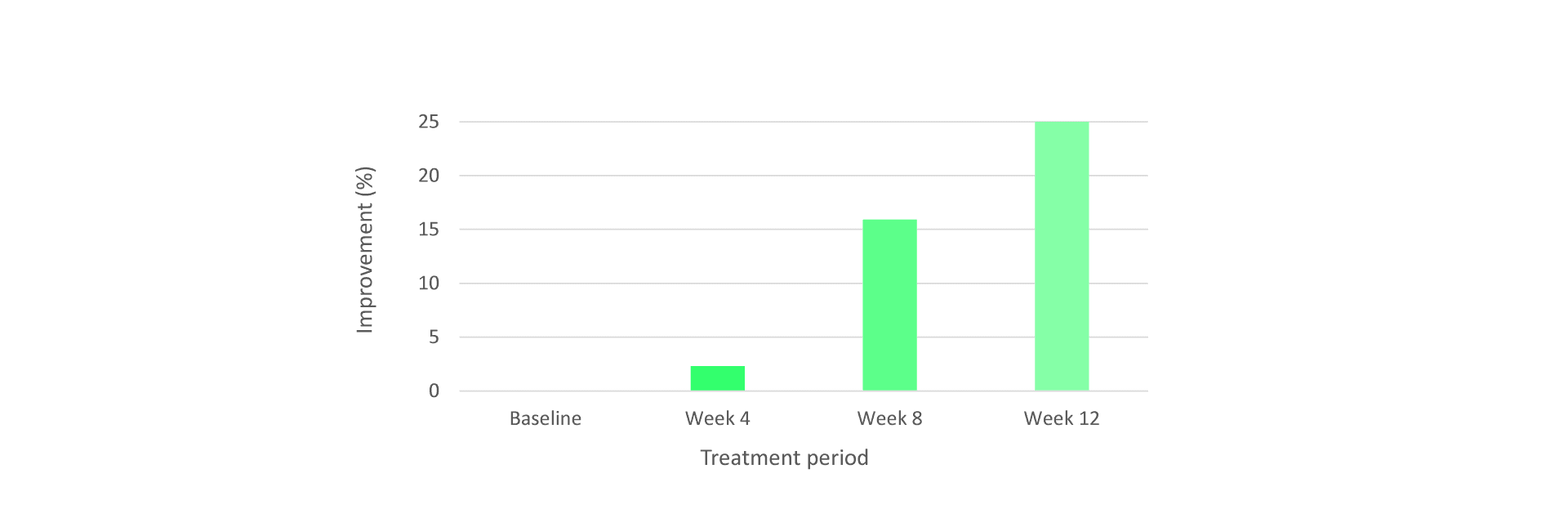

Sodium ascorbyl phosphate

STAY-C® 50 (INCI: Sodium Ascorbyl Phosphate) is a stabilized form of vitamin C known for its anti-oxidant, collagen-stimulating and skin-lightening activity. In an in vivo test, STAY-C® 50 showed comparable activity in reducing acne vulgaris relative to the prescriptive drug benzoyl peroxide at equal concentration. It also strongly inhibited the growth of C. acnes, the bacterium associated with the development of inflammatory lesions. Under usage conditions, STAY-C® 50 significantly reduced the incidence of inflammatory lesions on volunteers having acneic skin.

Figure 1: Time-kill study with STAY-C® 50 (pH 7) on C. acnes cultivated under anaerobic conditions.

Figure 2: Tested on 27 volunteers over 12 weeks of treatment using 3% STAY-C® 50 formulation. Papulae and pustules were counted by a dermatologist.

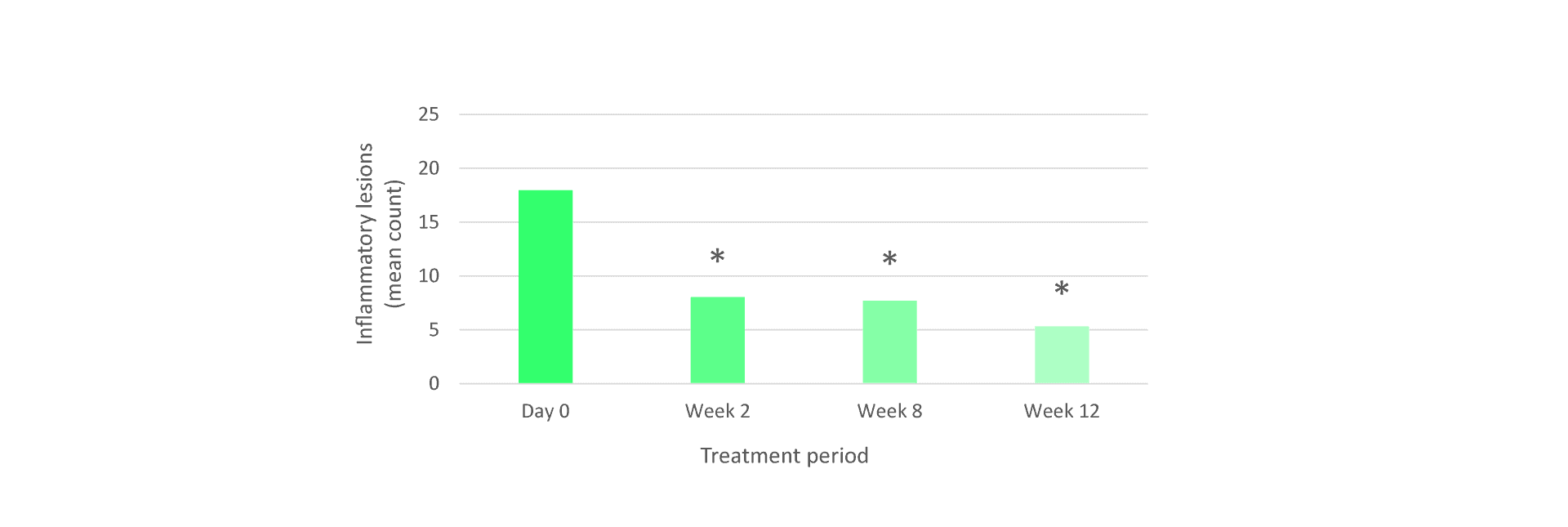

Niacinamide

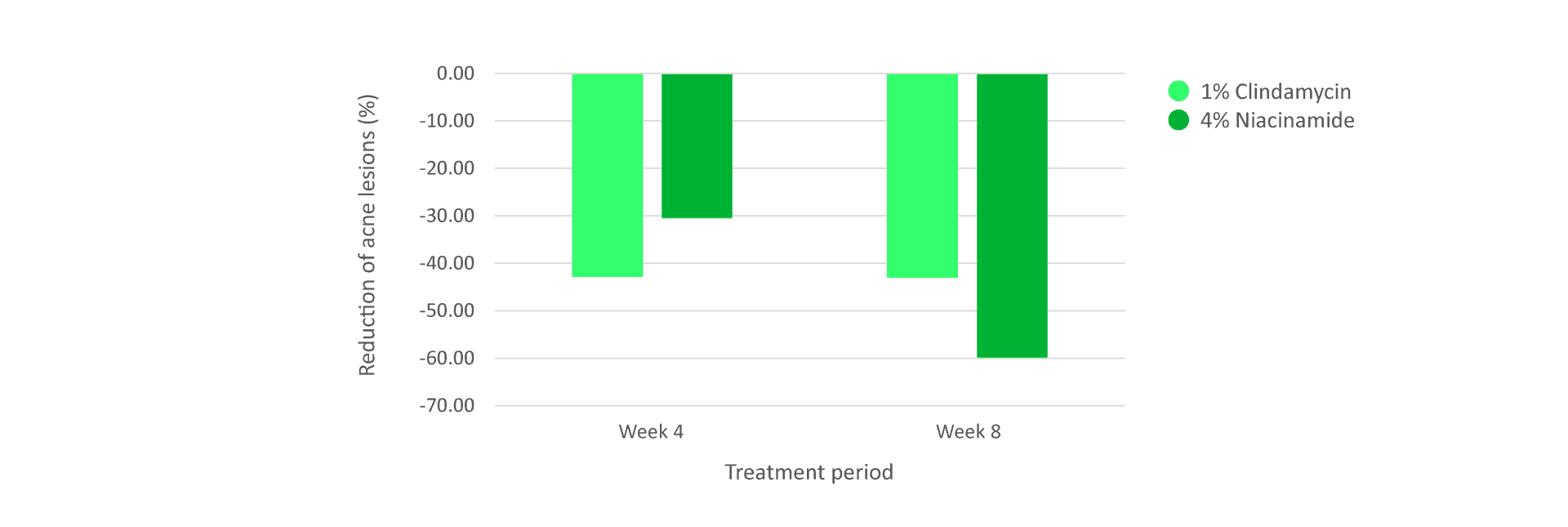

Niacinamide (vitamin B3) is known for its barrier-strengthening properties, and therefore its ability to reduce TEWL. Niacinamide also has positive effects on acne and some studies[8] have compared its efficacy with that of clindamycin, a prescriptive antibiotic. After 8 weeks of a treatment with 4% niacinamide, the suppression of inflammatory lesions was comparable to that of 1% clindamycin.

Figure 3: Tested on 76 volunteers with moderate acne (at least 15 papules or pustules) over 8 weeks of treatment.

Allantoin

Allantoin is a botanical extract obtained from common comfrey root. The many beneficial effects of allantoin have been shown by several studies. These include skin-soothing, moisturizing and keratolytic effects, an enhanced natural skin renewal process (desquamation), promotion of cell proliferation and wound healing, anti‐irritant effects, and protective effects on the skin[9]. Thanks to its benefits, allantoin is widely used to treat skin wounds, ulcers and burns, but also skin diseases such as dermatitis, psoriasis, impetigo and acne. Due to its soothing and wound-healing properties, allantoin is well-suited for helping to alleviate acne scars and reduce skin irritation.

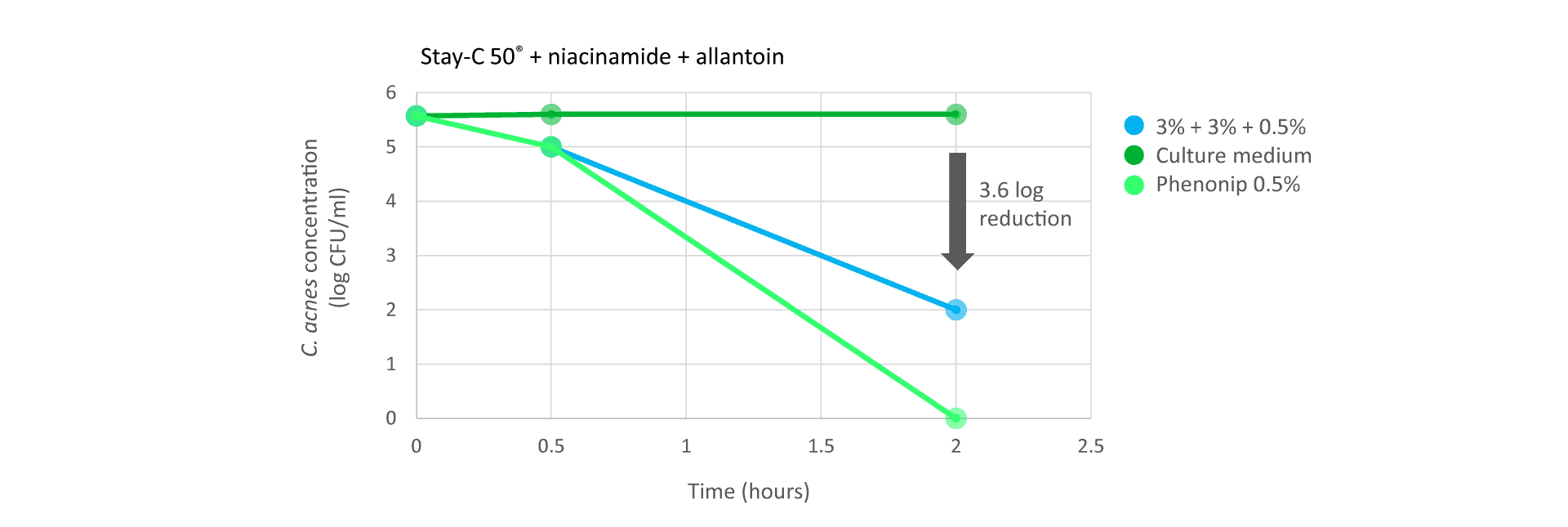

Stay-C® 50 in combination with niacinamide and allantoin

A recent study we performed surprisingly showed that Stay-C® 50, in combination with niacinamide and allantoin, can strongly inhibit the growth of an acne-associated C. acnes strain in only 2 hours. Interestingly, in the same experiment, none of the substances taken singularly were able to achieve the same result as the combination. Far from it! Niacinamide and allantoin have not been able to inhibit the growth of the bacterium at all. In addition, the combination of the three substances even outperformed 0.5% salicylic acid, which was tested in the same set up. This surprising result suggests that a combination of Stay-C® 50 with niacinamide and allantoin might be an effective treatment to reducing the abundance of pathogenic C. acnes strains on acneic skin, as well as to counteract the other exacerbating factors linked to the pathogenesis of acne, thanks to the benefits provided by the singular components of the combination.

Figure 4: Time-kill study using STAY-C® 50 (3%) in combination with niacinamide (3%) and allantoin (0.5%) on C.

acnes cultivated under anaerobic conditions.

Additional cosmetic benefits

The two vitamins STAY-C® 50 and niacinamide in combination with allantoin target different steps of acne formation. The antimicrobial effect, as well as the anti-oxidant effect avoiding the peroxidation of excess sebum, is attributed to STAY-C® 50. Allantoin – due to its keratolytic effect – promotes the shedding of dead skin cells, reducing the development of comedones, and at the same time helps the scar-healing process. Niacinamide can help further reduce inflammatory lesions in acne and strengthen the skin barrier, making it more resilient.

In addition, the combination provides enormous potential for the removal of unwanted and tedious side effects typical of standard acne treatments.

Age spots and uneven skin tone are not only signs of premature skin ageing due to extended UV light exposure, but hyperpigmentation is also a possible sequel to acne, referred to as PIH as mentioned earlier.

PIH can occur in all skin types, but is more common in people from Asia, Africa and indigenous Indian background. STAY-C® 50 and niacinamide can address these concerns, having proven activity against both acne and hyper-pigmentation.

Figure 5: Clinical evaluation of skin-whitening effect of STAY-C® 50. Tested on 39 volunteers over 12 weeks of treatment with 3% STAY-C® 50 formulation.

Conclusion

STAY-C® 50, niacinamide and allantoin have demonstrated anti-acne activity that is equal or even superior compared to classic or prescription anti-acne treatments. The proposed solution interferes with acne pathogenesis at different steps to maximize the potential for improvement, and specifically addresses the concerns of adults who look for milder but effective anti-acne care and want to gain even pigmentation/skin tone at the same time.

Our current understanding of the diversity of C. acnes strains and the involvement of specific strains in acne physiopathology suggests that individualized acne therapies targeting only the pathogenic strains could be developed. An interesting approach involves re-establishing the population of beneficial C. acnes strains that are important for the maintenance of healthy looking and acne-free skin. The approach goes under the name of probiotherapy and consists of topical application of living bacterial compositions (probiotics). Stay tuned!

Hear from more of our experts in the Views from section on the Content Hub and follow us on Instagram to receive the latest updates.

References

1. Walsh, T. R., Efthimiou J. & Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 16, e23-e33 (2016).

2. Sardana, K. et al. Cross-sectional Pilot study of antibiotic resistance in Propionibacterium acnes Strains in Indian Acne patients using 16S-RNA polymerase chain reaction: a comparison among treatment modalities including antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide, and isotretinoin. Indian J. Dermatol. 61, 45-52 (2016).

3. Gollnick, H.P. From new findings in acne pathogenesis to new approaches in treatment. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 29 (Suppl 5), 1-7 (2015).

4. Dréno, B. et al. The Skin Microbiome: A new actor in inflammatory acne. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 21, 18-24 (2020).

5. Habeshian, K.A. and Cohen B.A. Current issues in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Pediatrics. 145(Suppl 2), S225-S230 (2020).

6. Leyden, J. J. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am. Acad. of Dermatol. 49(Suppl 3), S200-S210 (2003).

7. Bashir, S. J. et al. Cutaneous bioassay of salicylic acid as a keratolytic. Int. J. Pharmacol. 292, 187-194 (2005).

8. Shalita, A. R. et al. Topical nicotinamide compared with clindamycin gel in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. Int. J. Dermatol. 34, 434-437 (1995).

9. Savic, V. et al. Comparative study of the biological activity of allantoin and aqueous extract of the comfrey root. Phytother. Res. 29, 1117-1122 (2015).