Dr Barbara Brockway looks back on the development of Pre, Pro and Postbiotics with a view to understand how these formulations may be at the heart of rebalancing the microbiome.

Towards the end of my first blog on The Secret Life of Skin, titled ‘Is the microbiome-selfie set to revolutionize human health?’, I pointed out that, as there is no single or ideal skin microbiome to strive for, the focus has turned to developing products to maintain, strengthen or gently rebalance the skin microbiome. Our knowledge of the skin microbiome’s many different ecosystems is rapidly expanding. This is leading to a greater understanding of the ways that products can help address imbalances (dysbiosis) especially those that are critical for health, cosmetic or our general wellbeing.

The complex microbiome

The causes of microbiome dysbiosis and the consequential effects are complex. Genomics is giving us some insights into why dysbiosis can occur in one group of individuals and not in others. For example, genetic sequencing has shown that P. acnes, isolated from acne lesions, is a subtly different and a more harmful strain of the P. acnes that lives harmlessly on nearly everyone’s skin.[1] This explains the paradox that it can cause acne in some yet live harmlessly on nearly everyone’ skin. (Note that although many of us still talk about P. acnes, Propionibacterium acnes was reclassified in 2016, so its correct name is now Cutibacterium acnes or C. acnes ).

Malassezia restricta, the fungus normally associated with scalp dandruff, provides another fascinating example of how genomics helps to explain microbiome dysbiosis. In this case, studies on the gut microbiome have linked a genetic weakness in a human gene, which is known to be important for immunity to fungi, to higher levels of Malassezia restricta on the gut surface[2]. It is intriguing to read how individuals with this genetic weakness are more likely to suffer from chronic stomach conditions, such as Crohn’s disease. Separate research shows groups of dandruff sufferers have higher ratios of the Malassezia to Propionbacterium (Cutibacterium) and Propionbacterium (Cutibacterium) to Staphylococcus on their scalps.[3] It is important to note here that unlike the more harmful strain of P. acnes (C. acnes) isolated from acne lesions, Malassezia restricta may not be a ‘bad’ microbe. Large numbers of healthy people have Malassezia restricta living harmlessly in both their gut and their scalp microbiome so Malassezia restricta may play an essential role in the overall health of the local microbiome or may at least be benign.

As has been discussed before on The Secret Life of Skin, the terms ‘good’ and ‘bad’ microbes can be too simplistic and possibly misleading. Researchers studying the gut speculate that the defective gene allows the population of Malassezia restricta to increase above normal levels, causing the dysbiosis in the gut microbiome. It is the dysbiosis that causes the stomach conditions. Similarly, researchers studying the scalp associate dandruff with the dysbiosis due to increased relative levels of Malassezia restricta, and they go on to link this change in the microbiota with less microbial synthesis of biotin and other vitamins. In both situations it is felt that the symptoms will be alleviated by gently rebalancing the local microbiome.

Formulating with Prebiotics, Probiotics and Postbiotics to control dysbiosis

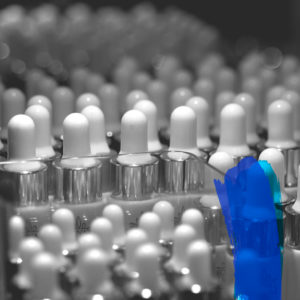

So how can cosmetic products gently rebalance skin microbiome dysbiosis? And, does the promise of Pre, Pro and Postbiotics live up the hype? Learning from ecology where some species (keystone species) have disproportionately large effects on their natural environment relative to their numbers, product developers have quickly turned to Prebiotics, Probiotics and Postbiotics, as natural approaches to correcting dysbiosis. Their strategies are to selectively feed key microbes (Prebiotics), to provide key microbes (Probiotics) or to deliver the materials microbes produce, which stabilises the skin microbiome (Postbiotics).

Great care must be taken when using these three terms as their original meanings are gradually being lost in the beauty industry’s hurry to develop new products. Prebiotics, Probiotics and Postbiotics relate closely to the microbiome they address. A dietary Prebiotic, therefore, may not be a skin Prebiotic. In cosmetics, the term “prebiotic ingredient” is used in a broad context, i.e. for substances that benefit beneficial bacteria or as substances produced by microorganism. Several food related ingredients such as yogurt powder, alpha-glucan oligosaccharide, inulin, lactic acid and lactobacillus ferment are also cosmetic ingredients often associated with probiotic or prebiotic products, indicating that they are good for both beneficial gut and skin microbes.

Prebiotics

The term Prebiotics was first coined back in 1995 for non-digestible food ingredients, which benefit the host by encouraging certain gut bacteria. Prebiotics were

then simply considered as ”food for beneficial microbes”. These early dietary Prebiotics were mostly short chained carbohydrates and included: resistant starch; pectin; beta-glucans; xylooligosaccharides (XOS) polymers such as fructans (fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin); galactans (galactooligosaccharides (GOS)); and carbohydrates derived from fibre.

To feed useful gut microbes living deep in the digestive tract, dietary Prebiotics need to resist being digested in the stomach. To this end, some ingenious forms of protective encapsulation are being developed, which may have useful functions in cosmetics.

Some diets, rich in Prebiotics, are reported to encourage the gut microbiome to ‘thicken’ and have accompanying health claims. Naturally, some regulatory authorities are concerned about these claims and so insist that beneficial health effects must be documented for a substance to be considered a prebiotic. In the EU, any health message carried by food requires assessment of the science by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and authorization by the European Commission. So far, only a few prebiotic health claims have been approved, for example chicory inulin. The situation in cosmetics is not as well defined but is equally contentious.

Probiotics

Originally, Probiotic referred to live microorganisms, which, when swallowed, deliver health benefits by being beneficial to the gut. Again, as with Prebiotics, Probiotic claims are contentious and of the more than 400 health claim applications with probiotics, received by the EFSA, only one was authorized. The most common reason for rejection was the insufficient demonstration of the health claim. Probiotic cosmetics based on the live bacteria associated with healthy foods such as Bifidobacterium spp, Lactobacilli and Saccharomyces boulardii are becoming popular[5]. Mother Dirt includes live Nitrosomonas eutropha, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium, which has been studied with respect to Nitric oxide (NO), and its consequential anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory properties. It is argued that the number of ammonia-oxidizing bacterium on skin (and therefore the amount of NO produced on skin) has been gradually reduced through modern hygiene practices i.e. through over washing and the use of an array of products and detergents on our skin. Restoring Nitrosomonas eutropha to the skin microbiome may indirectly bring about a range of cosmetic benefits by simply reducing inflammation[6].

Formulating live microorganisms into mainstream cosmetics into mainstream cosmetics is extremely problematic. Safety regulations require cosmetics to pass the micro-hostile challenge testOnce passed, the live microbes need to survive in the product for long periods, as c can have shelf-lives of 30 months. Despite these and other difficulties, there is now an increased number of Probiotic beauty products on the market. One such product claims 50 million probiotic microbes are activated when their Probiotic serum touches your skin. Some Probiotic cosmetics are made with inactivated microbes rather than with living microbes. Interestingly, the encapsulation methods mentioned earlier, that protect dietary Probiotics as they pass through the stomach, could also be used to protect live microbes in topical products. Close inspection of ingredient lists generally shows that many of these Probiotic cosmetics are based on microbial ferments, often as extracts or as lysates (so are in fact Postbiotics).

Developers brave enough to formulate with live microbes should learn lessons from faecal transplantation, which has recently been hitting the headlines. In order to provide enough ecological competition to displace pathogenic bacteria such as Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), medics transfer very high levels of live gut microbes from healthy donors. These faecal transplants are already in established interacting communities. In practice therefore, expecting single dominant microbe species, such as those in Probiotic foods and drinks, to correct gut dysbiosis is a much bigger-ask than you might expect, which might explain why there are so few supporting scientific publications.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics is a more recent term, which is being used to define metabolites and/or cell-wall components from cultures of Probiotics that selectively influence the microbiome for healthier outcomes. Many of the microbial ferment lysates and extracts in Probiotic cosmetics can therefore be thought of as Postbiotics.

Supplying the substrates and or antimicrobials made by a microbe would have similar effects to increasing the microbe’s numbers in a community. Perhaps many of the reported health benefits of fermented milk products, such as live yogurt and Kefir, are due more to cell debris and the products of fermentation, than to the live microbes that may survive digestion. Questions of why microbes, which are easy to commercially culture in milk, should confer cosmetic benefits have led to investigations into fermenting substrates found in skin, such as fats and glycerin with microbes associated with skin. The resulting Postbiotics are proving to be powerful active ingredients, in one case C. Acnes ferment has been shown to suppress community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)[7].

The opportunities and challenges ahead

The microbiome is proving to be very important for skin health and offers opportunities for even better cosmetics. More research is needed but the data available strongly suggests that this invisible protective shield will benefit from being supported and dysbiosis, rather than ‘bad’ microbes, can be the underlying cause of some skin problems. Learning from ecology, increasing biodiversity and so strengthening the microbiome will help it to gently rebalance itself.

Chief among the challenges facing the industry is how to protect the microbiome while complying to regulations which, for sound safety reasons, require products to be preserved and kill microbes in order to pass the micro challenge. This begs the other question – what effect are the cosmetics we currently use having on the microbiome?

The microbiome is a dynamic living shield. Its intrinsic metabolism and cell to cell communication, may lead to exciting new improved cosmetics. For example, we are seeing Prebiotics being used in cosmetics to help strengthen the integrity of the microbiome. The authorities are reluctant to allow these claims without clear substantiation, which is driving deeper research into how Prebiotics are metabolized by the microbiome. In the future we may see new types of cosmetic ingredients, which use the microbiome to convert them into active forms similarly to how skin enzymes are now used to convert vitamin esters into their most active forms. Microbiome metabolism may also explain the paradox of why cosmetics can be more effective on some people than on others and so lead to more personalised skin care. The microbiome could also be the key to managing some types of sensitive skin. Research is already showing how the microbiome primes our immune system and regulates inflammation.

Provided the industry clearly communicates to consumers, avoids inappropriate and loose use of the term “probiotic” and recognizes the importance of the strain specificity and dose etc., the next generation of cosmetics are all set to make a huge impact on skin health.

[1] Stacey L. Kolar, Chih-Ming Tsai, Juan Torres, Xuemo Fan, Huiying Li., and George Y. Liu. Propionibacterium acnes–induced immunopathology correlates with health and disease association. JCI Insight, 2019; 4 (5) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124687

[2] Martina Pellicciotta, Rosita Rigoni, Emilia Liana Falcone, Steven M. Holland, Anna Villa and Barbara Cassani. The microbiome and immunodeficiencies: Lessons from rare diseases. Journal of Autoimmunity Volume 98, March 2019, Pages 132-148, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2019.01.008

[3] Rituja Saxena, Parul Mittal, Cecile Clavaud, Darshan B. Dhakan, Prashant Hegde, Mahesh M. Veeranagaiah, Subarna Saha, Luc Souverain, Nita Roy, Lionel Breton, Namita Misra and Vineet K. Sharma. Comparison of Healthy and Dandruff Scalp Microbiome Reveals the Role of Commensals in Scalp Health. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018; 8: 346. Published online 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00346

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/27/style/gut-health-skin.html

[5] Gibson GR., and Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995; 125 (6): 1401–1412. https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/125/6/1401/4730723?redirectedFrom=fulltext

[6] Lee NY., Ibrahim O., Khetarpal S., Gaber M., Jamas S. , Gryllos I., and Dover JS. Dermal Microflora Restoration With Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria Nitrosomonas Eutropha in the Treatment of Keratosis Pilaris: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. Mar 2018, 17(3):285-288] https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/29537446

[7] Muya Shu, Yanhan Wang , Jinghua Yu, Sherwin Kuo, Alvin Coda, Yong Jiang, Richard L. Gallo, Chun-Ming Huang. Fermentation of Propionibacterium acnes, a Commensal Bacterium in the Human Skin Microbiome, as Skin Probiotics against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Published: February 6, 2013 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055380